There was one electrifying moment on last night’s Westworld: Dolores declared herself God with the power, knowledge, and ability to choose who lives and who dies. It sent my imagination on a powerful journey: what would the world look like if we replaced all the old white men in power with righteous rape survivors? Coming off the Cosby conviction last week and Larry Nassar’s before that, the force of it ran through me like a lightning bolt. Yes! I want to see this new world order!

This was Dolores’ episode as we saw her gather an army, expose other hosts to the truth (including the comically ignorant/hapless/confused Teddy), and take her place as leader of a new world order. However, the episode covered more than the fulfillment of Dolores’ righteous promise and revenge fantasy. We spent a lot of time with the Dolores of the past, learning what she knows about the founding of Westworld, her origins, and the connection between her and William.

“You really are just a thing,” a young William tells her toward the end, “I can’t believe I fell in love with you.” And in this moment, William completes his transition from protagonist to villain, going completely to the dark side. And that’s the genius of the Westworld. It takes old sexist tropes – women as objects only valuable for their sexuality – and makes them both true (Dolores is supposed to be a dumb sex robot after all) and so clearly wrong and evil (what sort of person would treat her like that?).

“Misogyny seems to be the source of the poison well this violence draws on. But all these toxic streams—white nationalism, fundamentalist religion, gun fetishism, whatever—do the same work.” – @VICE https://t.co/arbnKopoL4

— The Mask You Live In (@MaskYouLiveIn) April 25, 2018

And didn’t this scene read like so many bad break ups? The disillusioned man retreating into misogyny to objectify and dismiss his former love object? It felt the same as the end of the viral short story Cat Person, the same as the countless memes of dating-app conversations (Sample – Him: U r hot. Her: No thank you Him: You’re a stupid slut and should be ashamed of your yourself), the same of so much IRL. The show is exposing this behavior as based on the rejection of women’s personhood, and showing how it is both wrong and dangerous.

But that was in the past. The current William, the Man in Black, is now on a what appears to be a redemption narrative. And in this narrative, I guess we’re supposed to watch William overcome the traps that Ford left him and find them both so incredibly clever. So masculine. So strong. My problem is that this storyline has white supremacy written all over it. The Man in Block conscripts a Mexican sidekick who’s limited to the role of helper. And the two of them set off and soon find a town on fire. It appears that the Mexican bandits have taken over! With no guests or computer scripts to stop them, the Mexican “bandits” do the only thing their (white) programmers have taught them: they kill themselves! Because what’s a brown person for but to teach some white people some things? The intense violence against these brown men and the way they stay as simple pawns in white men’s machinations despite all the supposed upheaval in the park has me so tired.

Here we have a whole show looking at the dark side of humanity but it’s set in some imaginary post-racial world where no one ever talks about race. Yet the playground for the rich and debauched is set in the starkest of racial environments – the imaginary old west – where whiteness equates to goodness, Mexicanness is dirty and savage, and Native Americans are so foreign as to serve only as the other. One can only hope the showrunners have plans to right these wrongs and prove that their imagined, debased human world isn’t so post-racial after all.

But I digress. Enough about problematic, no-matter-the-timeline William. We’re all here for Dolores, looking to see if she can outgrow her programming. In this episode, we see how she was forged in patriarchy – created as a sexbot to get investors for her (pimps) creators. But we also see Arnold shielding her in the early stages of the park, saying that something is different about her, showing her where he plans to bring his family.

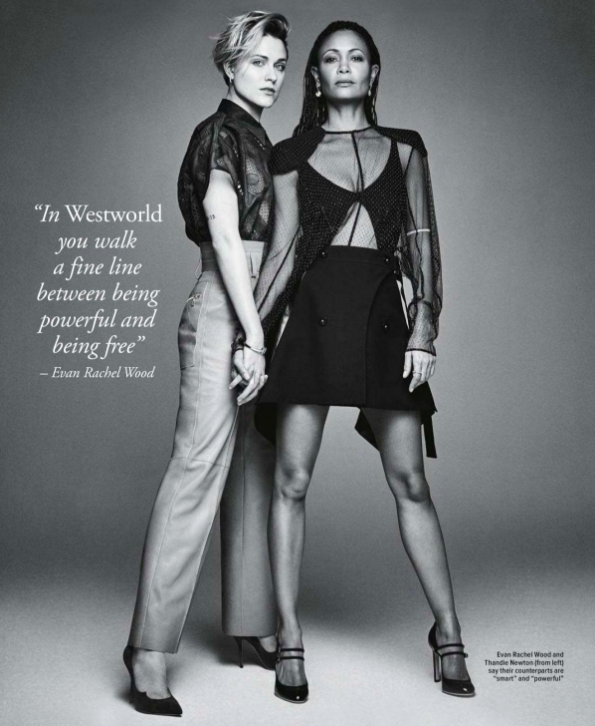

So can Dolores create a different way of being? Can she escape the sexist worldview that forged her and create a new destiny? Perhaps the clearest insight into this question is when she crosses paths with Maeve. These two women are the driving force of the show, the heroines we root for, week in, week out. Yet when they meet, the outcome is unclear and after thinking about it, I like that.

Maeve and Dolores offer us two different but compelling narratives of disruptive womanhood and the show makes space for both of them. Yes, they were each integral to overthrowing the old park but now they chart such different courses. Maeve defines success in a way none of the parker creators would – finding her robot daughter and ignoring the broader struggle around her. Dolores, on the other hand, plays into the war/power struggle narrative of Westworld but does so to free her kind, taking on the community’s struggle and making it her own. By having Maeve and Dolores engage in dialogue, but not resolve their differences, the show validates both of them. It refuses to say one of them is better than the other and breaks the single story around womanhood. Here’s to more shows that give women the power to create their own narrative.

This post originally appeared on therepresentationproject.org.

0 Comments